List of World War I memorials and cemeteries in the Somme

This article lists the memorials and cemeteries around the area of the river Somme.

Memorial to the Liverpool and Manchester Pals at Montauban

[edit]| Memorial to the Liverpool and Manchester Pals at Montauban |

|---|

Montauban is a village about 10 kilometres east of Albert. It lay close behind the German front-line in 1916 and was strongly fortified. On 1 July 1916, the first day on the Battle of the Somme, the village was seized by the British 30th Division in one of the few successful British advances of the day and in the village there is a memorial to the Liverpool and Manchester 'Pals', who, as part of the 30th Division, were the first to reach the village. Montauban was to remain free until the end of March 1918, when it was retaken by the Germans in their "Spring Offensive", to be liberated again in August 1918. This memorial includes the inscriptionThis is written in English and French. The memorial stone was unveiled by Major General Peter Davies, Colonel of the King's Regiment, on 1 July 1994. On one face the memorial carries the Liverpool Service Battalions' cap badge and on the other that of the Manchester Battalions.[1][2]  |

7th Yorkshire Regiment Memorial at Fricourt

[edit]| 7th Yorkshire Regiment Memorial at Fricourt |

|---|

| File WO 32/5873 held at The National Archives at Kew covers the 7th Yorkshire Regiment memorial at Fricourt. The memorial stands in the grounds of the cemetery at Bray Road in Fricourt and remembers those of the 7th Battalion, Alexandra Princess of Wales Own Yorkshire Regiment who fell in the Fricourt area on 1 July 1916. |

Statue of Marshal Foch at Bouchavesnes

[edit]| Statue of Marshal Foch at Bouchavesnes |

|---|

| The village of Bouchavesnes, with its neighbour Rancourt, was of great strategic importance given their position on the main Baupaume to Péronne road. On 12 September 1916, the French Chasseurs Regiment, led by the former Minister of War Messimy, charged and took the German position with fixed bayonets. Their advance was checked the next day following an intense German Artillery bombardment but the French held this line until the end of the Battle of the Somme. They had in fact advanced almost 10 kilometres from their start position at Maricourt on 1 July 1916. It was the Australians who finally liberated the village on 4 September 1918.

There is a statue of Foch in the village. Firmin-Marcelin Michelet was the sculptor. The French Army had done well in their sector and after the opening day they soon took Frise, Hérbecourt and Bernafay Wood as well as Assevillers. The 1st Colonial Corps took Flaucourt on 19 July and soon threatened Péronne. Biaches was taken then Barleux and the French Foreign Legion took Belloy-en-Santerre. Soon the plateau of Flaucourt had been conquered but none of these villages were taken without intense fighting and great loss of life. Bianchee, for example, was to change hands several times before being finally taken by the French on 19 July 1916. Once within sight of Péronne however, the French had to hold back, conscious that their left flank was exposed given the lack of progress on the British side. Rather than go for Péronne and head further northwards they moved in the direction of Chaulnes. [4]  |

Memorial to 18th Division at Thiepval

[edit]Memorial to the 46th Division at Bellenglise

[edit]| Memorial to the 46th Division at Bellenglise |

|---|

| File WO 32/5858 held at The National Archives in Kew has information on this memorial to the 46th North Midland Division at Bellenglise which is dedicated to the men who fell on 29 September 1918, when the division attacked the canal between Riquerval Bridge and Bellenglise and broke through the Hindenburg Line taking over 4,000 prisoners and 70 guns.

The file opens on 25 February 1919 when the request to erect the memorial was made. The memorial lies north of St. Quentin near the canal. The land was in fact given free of charge by the owner Monsieur de Chauvenet. The file closes on 5 June 1923. In the file there is a black-and-white photograph of the memorial and the inscription in English and French. We note that the memorial was sculpted by Harry Neme and Sons of Exeter. The unveiling took place on 4 October 1922. There are further memorials to the 46th Division at Vermelles, Gommecourt Wood and at the site of the Hohenzollern Redoubt.[6] |

Memorial at Flers

[edit]| Memorial at Flers |

|---|

Flers is the site of the memorial to the British 41st Division, the memorial featuring a sculpture of a fully equipped British infantry soldier, who faces towards the direction from which the 41st Division attacked.

This memorial was the work of the British sculptor Albert Toft. On the front of the memorial is inscribed The units comprising the division are then listed below; the 41st Division was a New Army Division and had only arrived in France some four months before their attack at Flers. There are no inscriptions on the sides or back of the memorial plinth, just the sculptor's name. The sculpture of the soldier replicates that which Toft executed for the war memorial at Holborn in London (Memorial to the Royal Fusiliers City of London Regiment). |

The New Zealand Memorial at Longueval

[edit]| The New Zealand Memorial at Longueval |

|---|

Sited near the South African Memorial at Delville Wood, the New Zealand Memorial at Longueval commemorates the area from which the New Zealand Division started their attack during the Battle of Flers-Courcelette on 15 September 1916, an occasion that saw the first use of tanks in warfare. Along with the British 14th and 41st Divisions, the New Zealanders entered the reclaimed village of Flers in triumph, preceded by one of the tanks used in the battle. The memorial itself was unveiled in October 1922. The Memorial takes the form of a column standing on a projecting base in which are set four panels. On the front of the column itself are engraved the wordsand the same is engraved in French at the back of the column. On the front panel is an exquisite sculptured design of a Maori carving surrounding the words "New Zealand" . On the back panel are engraved the words "New Zealand Division, Auckland, Wellington, Canterbury, Otago". On one side panel is engraved the following sentence and these words are reproduced in French on the other side panel.[8] At the base of the monument is engraved the phrase

File WO 32/5867 held at the National Archives in Kew gives us more background information on this memorial. We learn that the land on which this memorial stands was purchased from Vicomte Danger. |

New Zealand Memorial to the Missing at Caterpillar Valley Cemetery

[edit]| Caterpillar Valley (New Zealand) Memorial |

|---|

| This memorial is situated on a terrace in the Caterpillar Valley Cemetery, which lies a short distance west of Longueval, on the south side of the road to Contalmaison. Caterpillar Valley was the name given by the army to the long valley which rises eastwards, past "Caterpillar Wood", to the high ground at Guillemont. The ground was captured, after very fierce fighting, in the latter part of July 1916. It was lost in the German advance of March 1918 and recovered by the 38th (Welsh) Division on 28 August 1918, when a little cemetery was made (now Plot 1 of this cemetery) containing 25 graves of the 38th Division and the 6th Dragoon Guards. After the Armistice, this cemetery was hugely increased when the graves of more than 5,500 officers and men were brought in from other small cemeteries, and the battlefields of the Somme. The great majority of these soldiers died in the autumn of 1916 and almost all the rest in August or September 1918. The cemetery now contains 5,569 Commonwealth burials and commemorations of the First World War. 3,796 of the burials are unidentified but there are special memorials to 32 casualties known or believed to be buried among them, and to three buried in McCormick's Post Cemetery whose graves were destroyed by shell fire. On 6 November 2004, the remains of an unidentified New Zealand soldier were entrusted to New Zealand at a ceremony held at the Longueval Memorial, France. The remains had been exhumed by staff of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission from Caterpillar Valley Cemetery, Longueval, France, Plot 14, Row A, Grave 27 and were later laid to rest within the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior, at the National War Memorial, Wellington, New Zealand.

On the east side of the cemetery is the Caterpillar Valley (New Zealand) Memorial commemorating more than 1,200 officers and men of the New Zealand Division who died in the Battles of the Somme in 1916, and whose graves are not known. Both cemetery and memorial were designed by Sir Herbert Baker. [9]  |

Memorial to the 38th (Welsh) Division at Mametz Wood

[edit]Mametz Wood was to be the scene of some of the bloodiest fighting of the opening days of the Battle of the Somme as taking the wood involved advancing uphill and over open ground whilst facing heavy machine gun fire and artillery. By 12 July the woods had been cleared of Germans but at a heavy cost with over 4,000 Welsh deaths and casualties. The Mametz memorial takes the form of a Welsh dragon challenging the wood to its fore. At one side of the base is carved the regimental cap badge of the South Wales Borderers. The sculptural work was by David Petersen.

The 38th (Welsh) Division was very much the result of personal initiatives by Lloyd George and was the Welsh equivalent of the "Pals" battalions from the North of England. So awful was the fighting here that a Welsh soldier, Wyn Griffith, described it as "the horror of our way of life and death and of our crucifixion of youth".

Joint Memorial to the Black Watch and Cameron Highlanders

[edit]| Joint Memorial to the Black Watch and Cameron Highlanders |

|---|

| This memorial at High Wood commemorates the action of the 1st Cameronians and 1st Black Watch there in the fighting in September 1916.

File WO 32/5893 at the National Archives in Kew gives us some background information on the memorial. Originally these two units had erected a wooden cross on the spot in November 1916 but this was replaced in 1924 by the first of the permanent memorials at the edge of High Wood. This memorial can be seen today half-way along the south-eastern edge of the wood. We learn from the file that the spot chosen for the memorial was the position where the right of the 1st Black Watch joined the left of the 1st Cameronians when they both attacked High Wood on 3 September 1916[12] |

Australian First Division Memorial at Pozières

[edit]| Australian First Division Memorial at Pozières |

|---|

| The fighting in Pozières in 1916 was some of the most ferocious of the war and cost the lives of more Australians in a six-week period than the entire eight months of the Gallipoli campaign.

Pozières sits on a high ridge between the strategically important towns of Albert and Bapaume. As the highest point on the 1916 Somme battlefield, the town was a vital objective – whichever side controlled it would have unimpeded views of much of the enemy front. The Allies expected to capture the town (and beyond) on 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, but three weeks later it was still firmly in German hands. Australian troops arrived in the area on 14 July and immediately began preparations to attack Pozières. The town was the bastion of the German defensive line and was protected by the formidable 'K' and 'Pozières' trenches in front of the village and two solid trenches behind, designated 'OG' (Old German) 1 and 2. Before the war a windmill had stood to the north-east of the town; it was destroyed early in the fighting but its foundations had been turned by the Germans into a formidable machine gun post.  The Australian 1st Division and the 48th (South Midland) Division attacked Pozières in the early hours of 23 July 1916 and captured the town after ferocious fighting. The Germans launched several counter-attacks in a desperate effort to wrest control from the Australians, but all were repulsed. The Germans then switched tactics: if they couldn't force the Australians out of Pozieres, they would destroy them. They launched one of the heaviest artillery barrages of the war and pounded the Australians incessantly: at the height of the bombardment the shells rained down at the rate of 20 per minute. After three days the 1st Division had lost 5,285 men and the rest were exhausted. The division was withdrawn and replaced by the 2nd Division. German pressure remained relentless and after 10 days the 2nd Division had lost 6,848 officers and men. It too was withdrawn and replaced by the 4th Division. This cycle continued until 3 September 1916. Each Division fought until exhausted and was then replaced. When the replacement division was itself exhausted, the original division was rotated back into the line. Thus were the 1st, 2nd and 4th Divisions used as a battering ram against the German strong points at Pozières until they were almost destroyed. More than 50% of the Australians who fought at Pozières were killed, wounded or captured and five Victoria Crosses were won by Australians during the relentless fighting. When entering today's Pozières one is immediately reminded of the Australian's efforts there and one is greeted by a large painting depicting an Australian soldier (See photograph in "Gallery of images"). The memorial itself comprises an obelisk and followed a design that was to be used by the Australians for several of their monuments and a plaque in English and French salutes their achievements and lists their battle honours.  Pozières was retaken by the Germans in their "Spring Offensive" of 1918 and recaptured by the 17th Division on the following 24 August. [13][14] |

The Tank Memorial at Pozières

[edit]| The Tank Memorial at Pozières |

|---|

The Tank Corps Memorial is located on the Albert-Bapaume road north-east of Pozières village.

It was in 1919 that the Tank Corps applied for permission to put up a memorial on this site. They proposed to erect a granite obelisk on a plinth with four models of tanks at each of the four corners of the obelisk's base. The proposal was accepted by the British Battle Exploit Memorials Committee and by the French authorities. The memorial was unveiled by Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas L. N. Morland in July 1922. Two bronze plaques on the memorial are inscribed with the names of battles on the Western Front in France in which the tanks were used from September 1916 to the Armistice in November 1918. is inscribed on the first plaque with on the second.  It was from near the memorial's location that tanks first went into action with the British Army as a new, surprise weapon against the Germans and only a few miles south of this memorial tanks were used at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette from 15 to 22 September 1916. One interesting feature of the memorial is the boundary "fence" around the obelisk. In the application to build the memorial, a fence was suggested as a way of keeping cattle away from the plinth of the memorial and this fence was to comprise ten upright 6-pounder tank gun barrels with tank chains. The small-scale replicas of some of the tanks used and positioned at the four corners of the memorial are Mark IV and V Heavy tanks and a Mark I Gun-carrier tank and a Medium A Whippet. From the Tank Memorial there are excellent views across the battlefields in all directions except back toward Albert as this view is blocked by trees. However, the elevated viewing platform at the 1st Australian Division memorial on the other side of the village can be used for views of Albert. [15] |

The Windmill Memorial at Pozières

[edit]

| The Windmill Memorial at Pozières |

|---|

A rough mound is all that remains of the windmill that stood here for centuries until 1916. It marks the highest point of the entire Somme battlefield (known as Hill 160). The Germans converted the ruins of the windmill to a machine gun post and concrete fortifications can still be seen on the mound. Thousands of Australians were killed and wounded in the surrounding fields whilst attempting to capture these formidable defensive positions. After the war the windmill site was acquired by the Australian Government and now stands as a memorial to the 23,000 Australians who were killed or wounded in the Pozières battle and a stone bench in front of the mound bears the following inscription

The site is flanked by the flags of Australia and France, and two large stones with the insignia of the Australian Imperial Force stand by a walkway which leads to the stone bench. Behind this is a Ross Bastiaan bronze plaque, similar to those located at other sites of particular significance to the Australian forces. The plaque, which was unveiled by Lieutenant-General J.C. Grey on 30 August 1993, gives information about the battle, stating that the Australians went into battle here on 23 July 1916 and fought until they were relieved on 5 September by the Canadians. It also has a relief map of the Somme area. Behind the bench and bronze plaque is some uneven ground and some concrete remnants can be seen, presumably of the German fortifications on the site of the windmill. [16] |

The Mouquet Farm at Pozières

[edit]The Kings Royal Rifle Corps Memorial at Pozières

[edit]| The Kings Royal Rifle Corps Memorial at Pozières |

|---|

The Kings Royal Rifle Corps' chose this location for their regimental memorial in France shown above. It reads

Many of the battalions of the King's Royal Rifle Corps fought throughout the Battle of the Somme notably in High Wood and at Delville Wood.[18] |

The Pozières British Cemetery and the Pozières Memorial to the Missing

[edit]| The Pozières British Cemetery and the Pozières Memorial to the Missing |

|---|

The Pozières Memorial to the Missing surrounds the Pozières British Cemetery and covers the period in March and April 1918 when the Allied Fifth Army was driven back by overwhelming numbers across the former Somme battlefields at the time of the German's "Spring Offensive" and the months that followed before the "Advance to Victory" which began on 8 August 1918. The memorial commemorates over 14,000 casualties of the United Kingdom and 300 of the South African Forces who have no known grave and who died on the Somme from 21 March to 7 August 1918. Although the memorial surrounds a cemetery with many Australian graves, it does not bear any Australian names; the Australian soldiers who fell in France and whose graves are not known are commemorated on the National Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux. The cemetery and memorial were designed by William Harrison Cowlishaw with sculpture by Laurence A. Turner.[19] The memorial was unveiled by Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien on 4 August 1930.[20]

|

The Thiepval Memorial

[edit]| The Thiepval Memorial |

|---|

The Thiepval Memorial was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and is visible for miles around. It stands as a sombre reminder of the many soldiers who lost their lives on the Somme battlefields but who have no known grave. It is 150 feet high and its base measures 123 x 140 feet. On its white stone panels and mounted on sixteen piers are carved the names of over 73,000 soldiers, both British and South African, who were lost in this area between July 1915 and 20 March 1918. These names are given in regimental order and then within each regiment, by rank and name. Soldiers who went missing in this area from 21 March 1918 onwards are commemorated on the nearby Pozieres Memorial.

The memorial does of course record many of the soldiers who died on 1 July, the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Indeed, it is reckoned that 90% of the names recorded were men lost in the 1916 battle. The memorial was built between 1928 and 1932 and unveiled by the Prince of Wales on 31 July 1932. The memorial also serves as an Anglo-French Battle Memorial in recognition of the joint nature of the 1916 offensive and in the winter of 1932–33 it was decided that a small mixed cemetery would be made at the memorial's foot to represent the losses of both the French and British and Commonwealth Nations. Most of the graves are of unidentified soldiers. Amongst those remembered at Thiepval are Victoria Cross winners Private William Buckingham, Private William Mariner, T/Captain Eric Norman Frankland Bell, Private William Frederick McFadzean, T/Lieutenant Geoffrey St George Shillington and T/Lieutenant Thomas Orde Lauder Wilkinson.  |

Memorial to the men of the 36th (Ulster) Division at Thiepval

[edit]| Memorial to the men of the 36th (Ulster) Division at Thiepval |

|---|

The Ulster Tower Memorial commemorates the men of the 36th (Ulster) Division who fought not only here but in other battles and areas during the war. It is a copy of Helen's Tower which stands in the grounds of the Clandeboye Estate, near Bangor, County Down in Northern Ireland. Many of the men of the Ulster Division trained in the estate before moving to England and then France early in 1916.

The Tower is located very near to the famous Schwaben Redoubt (Feste Schwaben) which the 36th (Ulster) Division were allocated to attack on 1 July 1916. The Schwaben Redoubt was a little to the north-east of where the tower stands, and was a triangle of trenches with a frontage of 300 metres, a fearsome German strongpoint with commanding views. The tower, which is 21 metres (69 ft) high, was unveiled by Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson on 19 November 1921, at a ceremony also attended by French dignitaries. The tower was dedicated by the Primate of All Ireland, the Moderator of the Irish Presbyterian church and the President of the Methodist Church in Ireland. At the time it was described as the most imposing monument on the Western Front; and was the first permanent memorial on the Western Front. The plaque inside the tower which commemorates the opening, mentions that Lord Carson was initially scheduled to open the memorial but that due to ill-health he could not travel to France for the ceremony. Trees from Ulster were planted here by survivors from the 36th (Ulster) Division. At the entrance to the site, and on the right hand side, there is a flagpole flying the Union Flag, whilst on the left is a memorial plaque dedicated to the nine officers, NCOs and soldiers awarded the Victoria Cross (VC) who fought with the 36th (Ulster) Division during the war. This plaque was unveiled in 1951. Of the men commemorated, four were awarded the VC for actions on 1 July 1916; Captain Eric Bell (killed 1 July), Lieutenant Geoffrey Cather (VC awarded for actions on 1 and 2 July, killed 2 July), Private Billy MacFadzean (killed 1 July) and Private Robert Quigg. Robert Quigg survived the War, but was nearly killed ten years after the Battle of the Somme, when in 1926 he fell from a window of the Soldiers Home in Belfast, only narrowly missing being impaled on railings beneath. He eventually died in 1955. The Inscription on the Memorial reads

File WO 32/5868 held at The National Archives in Kew gives us further information on the Ulster Division Memorial. The file opens with a letter dated 7 April 1919 from James Craig who writes to the 36th (Ulster) Division Commanding Officer stating that he writes at the request of Sir Edward Carson to say that over £5000.00 had been subscribed to erect a suitable memorial to the 36th (Ulster) Division. The letter states that Thiepval would be the most favoured site for the memorial. The file follows progress in erecting the memorial and by November 1919 the idea of the memorial taking the form of a typical "Ulster" tower is being discussed. The file contains an architect's drawing of the proposed tower signed by J.A. Bowden M.S.A. and Major A L Abbot, architects. We also learn from the file that the tower was built by Messrs. Fenning & Co. Ltd. of Palace Wharf, Rainville Road, Hammersmith. W.6. We also learn that round the windows of the memorial chamber is inscribed[21][22] |

The Canadian Memorial at Courcelette

[edit]| The Canadian Memorial at Courcelette |

|---|

| The Courcelette Memorial is a Canadian war memorial that commemorates the actions of the Canadian Corps in the final two and a half months of the infamous four-and-a-half-month-long Somme offensive. The Canadians participated at the Somme from early September to the middle of November 1916, engaging in several of the battles-within-the-battle of the Somme, including actions at Flers-Courcelette, Thiepval Ridge and the Ancre Heights, as well as a small role in providing relief to the First Australian Imperial Force in the final days of the Battle of Pozières. The battles on the Somme were the first in which all four Canadian divisions participated in the same battle, although not together in a cohesive formation. The Canadian divisions suffered over 24,000 casualties.

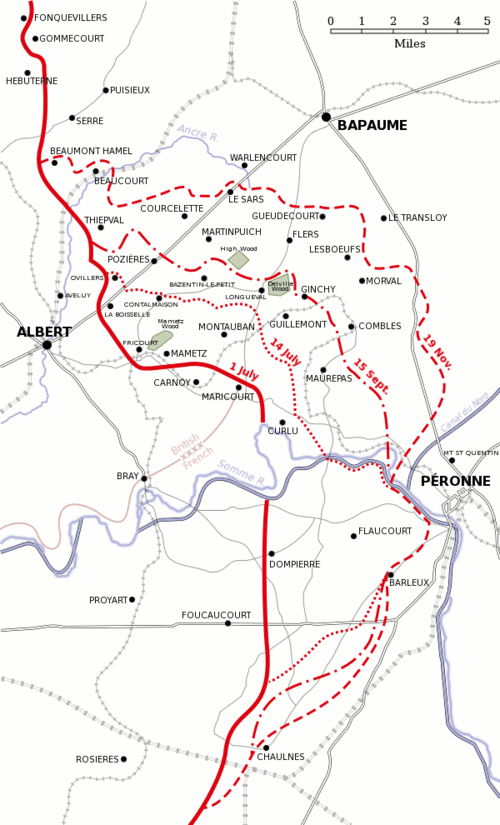

Courcelette is located to the north of the main D929 road between Albert and Bapaume and at the beginning of the Somme Battles in July 1916 it was well within German held territory (see map above). Indeed, it was not until mid-September that the Allies reached Courcelette and on 15 September 1916, the offensive which was to be known as the Battle of Flers-Courcelette was launched. It was fought on a wide front with the Canadians playing a major role and involved the first use of tanks. After Courcelette's capture it remained near to the front lines until the Germans withdrew to the Hindenburg Line early in 1917. In the German's "Spring Offensive" they retook Courcelette on 25 March 1918 and five months later it was retaken by the British as they advanced in the final few months of the War.

There are a number of cemeteries near Courcelette. To the west of the village is Courcelette British Cemetery, originally known as Mouquet Road or Sunken Road Cemetery and to the north lies the Adanac Military Cemetery. Regina Trench crossed the road a little to the south of the cemetery, and Courcelette Trench ran on the other side of the road from the cemetery. A Maple Leaf motif attached to the cemetery gates denotes the Canadian associations of this cemetery, the name being 'Canada' spelt backwards. Over 3,000 are buried here, around a third of whom are Canadian.[23] |

Memorials at Ovillers-la-Boisselle: The Lochnagar Crater

[edit]| The Lochnagar Crater |

|---|

The villages of Ovillers and La Boiselle are located either side of the main Albert-Bapaume road. Ovillers (which is properly known as Ovillers la Boiselle) lies to the north of the road, and La Boiselle to the south. On 1 July 1916, both villages were just behind the German front lines. The attacks here on 1 July were made by the 34th Division, with the 8th Division to their north in front of Ovillers. They met with little success, and casualty rates in the attacking battalions were extremely high. A number of mines were blown along the Somme front line and before the infantry went "over the top" and here two large mines were blown two minutes before the infantry attacked; at Lochnagar and Y Sap. The crater made at Y Sap has since been filled in, and no trace remains but Lochnagar crater remains as one of the best known sites in the 1916 Somme battlefield region. At Lochnagar it is possible to walk all around the edge of the crater left by the explosion, but access to the crater itself is not permitted. Two charges of ammonal (16,000 kilograms (36,000 lb) and 11,000 kilograms (24,000 lb) 20 metres (66 ft) apart) had been set off under a German position called Schwaben Hohe, and the crater originally measured some 100 metres (300 ft) across and 30 metres (100 ft) deep.

|

Memorial to the 102nd and 103rd Tyneside Infantry Brigades at La Boiselle

[edit]| Memorial to the 102nd and 103rd Tyneside Infantry Brigades at La Boiselle |

|---|

The Tyneside Memorial Seat, a memorial to the 102nd and 103rd Tynside Infantry Brigades was unveiled by Foch on 20 April 1922 and commemorates the Tyneside Scottish and Tyneside Irish Brigades' efforts to capture the ground either side of La Boisselle.

This memorial comprises a seat and bears a central plaque depicting a classical mounted warrior battling a dragon, whilst a weeping maiden looks on. There is also an inscription which reads The motifs of the two Brigades, officially the 102nd and 103rd Brigades, are displayed on the pillars flanking either side of the seat. File WO 32/5954 held at the National Archives in Kew covers this memorial and we learn that an application for approval of the memorial being erected was made on 4 September 1919 and that it was intended to replace the existing wooden cross of the 102nd Infantry Brigade, which it was agreed, in a splendid turn of phrase, "be abandoned to the processes of nature". The Tyneside Scottish and Irish battalions of the Northumberland Fusiliers were formed in 1914. The Tyneside Scottish were the 20th to 23rd Battalions and formed part of the 102nd Brigade, 34th Division. The Tyneside Irish were the 24th to 27th Battalion, and part of 103rd Brigade in the same division. Both Brigades were committed to the attack on La Boisselle on 1 July 1916, some elements of the Tyneside Irish attacking up Mash Valley, and the bulk of the Tyneside Scottish advancing from Tara Hill down into Avoca Valley. Casualties were very heavy. The Tyneside Scottish Brigade lost 2,324 officers and men, and the Tyneside Irish Brigade 1,968. Losses among senior officers were particularly heavy, with all four battalion commanders in the Tyneside Scottish Brigade being killed. In the Tyneside Irish Brigade the Brigade commander was wounded and three of the four battalion commanders were killed or wounded. The Tyneside memorial is on the western edge of the village of La Boiselle. [25] |

Memorial to the 19th (Western) Division at La Boiselle

[edit]| Memorial to the 19th (Western) Division at La Boiselle |

|---|

This memorial comprises a stone cross, with a butterfly on the top, the butterfly being the emblem of the division. The 19th Division had attacked La Boiselle in the early morning on 2 July 1916, and managed to take most of the village, although the Germans still held a line that ran through the church. The inscription at the top reads and shows that the memorial commemorates not only the attack on 2 July 1916, but also the actions of the 19th Division throughout the remainder of the Somme battles that year, up until 20 November. As well as La Boiselle, the names Bazentin-le-Petit (where the division fought on 23 July) and Grandcourt (where the division withdrew on 19 November, right at the end of the Somme campaign) are listed. On the base of cross are listed the units which made up the 19th Division; on the front these cover the Artillery, Engineers, Pioneers, RAMC and RASC, and on the other three sides the battalions of the three infantry brigades, the 56th, 57th & 58th. |

The 34th Division Memorial at La Boiselle

[edit]| The 34th Division Memorial at La Boiselle |

|---|

| Not far from the 19th Division Memorial is the 34th Division memorial. This is in the form of the figure of Victory, on a stone plinth, originally holding up a laurel wreath. This memorial was unveiled on 23 May 1923, by Major-General Sir Cecil Nicholson, who had commanded the division from 25 July 1916 until the end of the war (he had taken over after Major-General Ingouville-Williams was killed).

The 34th Division's Memorial commemorates the part that the 34th Division had in the heavy fighting in and around the area of La Boisselle in July 1916. The 34th Division had been raised as part of Kitchener's New Army and the Somme was to be their first battle. Formed for the most part by men from Tyneside it also had two battalions of Royal Scots from Edinburgh (One of which, the 16th was the footballers' battalion). As part of the great offensive on 1 July 1916, the 34th Division's task was to advance towards Contalmaison – the next village – taking La Boiselle, the Schwaben Höhe (Site of the Lochnagar Crater), Sausage Valley and the Sausage Redoubt. The attacks were met by a hail of fire from German defenders who had been waiting out the week-long bombardment in their shelters. By the evening when the 19th Division took over the front line, Schwaben Höhe and a foothold on the Sausage Redoubt were the only gains that had been made. La Boisselle was still very much in German hands. The memorial then features a bronze figure of "Victory" atop a plinth and incorporates the division's chequerboard emblem. The memorial is said to be located where the Divisional HQ stood in 1916. The division's units are listed on the side panels; infantry on the left and artillery and engineers on the right. The inscription commemorates the 34th Division (which included the Tyneside Scottish & Irish Brigades referred to earlier, see the Tyneside Memorial Seat). The memorial records that the division was engaged for the first time in battle near this spot on 1 July 1916. All 12 infantry battalions of the division were to be involved, in successive waves. In around 10 minutes nearly 80% of the men in the leading battalions had become casualties; mainly caused by German machine-guns. These, once the British barrage lifted, were able to sweep across No Man's Land (often wide here) and catch the advancing soldiers in the open. There was some success on the extreme right of the 34th Division frontage on 1 July, but in front of Ovillers and la Boiselle the only gains came in between Lochnagar and La Boiselle, where the 21st, 22nd and 26th Northumberland Fusiliers (the first two battalions from 102nd Brigade, the last from 103rd Brigade) started to advance the moment the mine at Lochnagar was blown. The troops took German trenches to the north and north-east of Lochnagar crater, around Schwaben Hohe and on the northern slopes of Sausage Valley. However, there were no reinforcements for the Divisional Commander, Major-General Ingouville-Williams, to deploy, and so the 19th Division were detailed to carry out an attack on La Boiselle after dark. They successfully took the village early the next day.[26] Ovillers is the village to the north of the D929. From the main road, there is a good view of the large Ovillers Military Cemetery. This contains the burials of nearly 3,500 soldiers, only 31% of which are identified burials. The cemetery is located in what was No Mans Land, and from the front of the cemetery, where a bank slopes down to the road, there are clear views of the Albert basilica to the right, of Mash valley in front, and the main road running on the spur ahead. Charles Edmonds, returning across this area on 16 July described it in "A Subaltern's War"

The cemetery was originally only a single plot, Plot 1, located a little back from the front right of the cemetery. This was started around August 1916, and used until March 1917. It was then quite small, less than 150 graves, but the cemetery was increased significantly after the Armistice. This was mainly as a result of bringing in bodies from the local battlefields of Ovillers, La Boiselle, Pozières and Contalmaison. This explains the high number of unidentified burials located here.[25] |

Serre Road

[edit]| Serre Road |

|---|

| Serre was not the place to be in 1914–18 and lest we had any doubts of this the approach to the village sees Serre Road Cemetery No.2 on the left and Serre Road Cemetery No.1 on the right but not before we see the mass of graves in the French Serre-Hébuterne Cemetery. No sooner have we absorbed this do we come across a rather forlorn little memorial to the York and Lancasters.

In 1916 Serre was to be hell for the British and Allied Armies, but the French had already seen many deaths there in the actions of 1915. In the village of Serre itself is the memorial to the 31st Division which consisted of Pals' battalions drawn from Leeds, Bradford, Barnsley, Sheffield, Durham and Accrington. The 31st Division were charged with taking the village and when they "went over the top" they were soon to lose over 5,000 men. Nearby is Hawthorn Ridge where a 45,000 pound ammonal mine was blown on 1 July 1916, one of the many detonations before the attack started which it was hoped would distract the Germans. The Accrington Pals, officially the 11th Battalion East Lancashire Regiment, were part of the 31st Division. They had served in Egypt in 1915/16, and then came to the Somme in the spring of 1916 taking over the trenches opposite Serre. At 7.30am on 1 July 1916 they were in the first wave of the attack from Mark Copse, and although they suffered heavily crossing No Man's Land, elements of the battalion under the commanding officer, Lt-Col Rickman, did reach the German lines. By the close of the day, however, they were forced back and had lost 584 officers and men out of 720 who had made the attack that morning. The Memorial was erected in the 1980s in the Sheffield Memorial Park, just behind one of the jumping off trenches from where the Accrington Pals advanced on 1 July. It is made from Accrington brick, and the ruined wall symbolises the ruined village of Serre. The British 31st Division was a New Army division formed in April 1915 as part of the K4 Army Group and taken over by the War Office on 10 August 1915. The division comprised mainly battalions from Yorkshire and Lancashire. |

The South African Memorial at Delville Wood

[edit]| The South African Memorial at Delville Wood |

|---|

Delville Wood was sometimes known as Devil's Wood, and the fighting there during the battle of the Somme was particularly ferocious and involved countless deaths. The majority of the wood was eventually taken by South African soldiers on 15 July 1916, and they held on grimly during numerous German counterattacks for six days, until they were relieved. The fighting went on until 3 September 1916.

In 1920, South Africa purchased the site considering it an ideal location for their National Memorial and it serves as a memorial to all those South Africans who gave their lives not only in the 1914–1918 war but also the Second World War and the Korean War. Delville Wood is located off the D20 that runs between Longueval and Guillemont. Opposite the South African Memorial there is a large Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery, the Delville Wood Cemetery. This is the third largest British cemetery on the Somme, with 5,523 graves. Almost all the burials are of casualties from the Somme during the period July, August and September 1916 and a high proportion of the bodies could not be identified. The memorial was unveiled in 1926 and its imposing entrance is surmounted by a statue of a horse and two men. This was based on the legend of Castor and Pollux and is an allegory representing the fact that both English South Africans and Boers had fought side by side. The names of areas where South Africans fought, including locations in France and Flanders, are inscribed on the memorial, and above the entrance arch are the wordsThe sculptor Alfred Turner was selected by Sir Herbert Baker to execute the Castor, Pollux and Horse sculpture and this led to his participation in the Cape Town and Pretoria War Memorials which used the same Castor and Pollux work. A plaster cast of "Dioscuri", the title of Turner's work, was shown in the forecourt of Burlington House in 1925 before the bronze was despatched to France the next year and unveiled on 10 October 1926 by the widow of General Botha. Two full-size bronze replicas went to South Africa in April 1928, one being erected in front of Capitol Buildings in Pretoria and the other in Cape Town. A bronze model was also placed in the Queen's Hall of the South African Houses of Parliament. 10 October was chosen as the unveiling date for the Delville Wood memorial as this was the date in 1899 when the first shot was fired in the South African War and the date in 1908 of the National Conference which brought the Union of South Africa into being. In file TGA 8713.1.7 at Tate Britain Archive there is a copy of the unveiling ceremony programme of Sunday 10 October 1926. This describes the bronze sculpture as follows Also in the Archives are file TGA 8713.1.8. "The Delville Wood Memorial Book" in which one can read the text of some of the speeches made including that of Joffre who represented France and that of Field Marshal Earl Haig and file TGA 8713.1.9 which contains the final report of the South African National Memorial (Delville Wood) Committee of July 1931. This is a memorial to those who died, rather than to those with no known grave. Those South Africans whose bodies were never identified and were listed as "missing" are inscribed on the Thiepval Memorial and other "Memorials to the Missing". Behind the memorial is a museum. This is relatively new, with a stone laid on 7 June 1984 to commence building work and the building itself was opened on 11 November 1986, by Mr. P.W. Botha. In the "Gallery of Images" at the end of this entry there is a photograph of the plaque which commemorates this opening. The museum is hexagonal in structure, and inside are four large bronze panels on the outer walls. The first (to the left from the entrance) contains 16 friezes depicting various aspects of the 1914–1918 war, whilst the next is devoted to the particular actions at Delville Wood in the six days from 14 to 20 July 1916. The third bronze also deals with the 1914–1918 war, whilst the fourth covers the Second World War. Several of the inner walls contain large windows, and etched on the glass are the battle honours of the South African forces. Both the memorial and the museum stand within the re-grown wood, and it is possible to walk along the same "rides" or tracks that used to exist before and during the war. In the spirit of the time, these were given street names by the soldiers who fought here. For example, there are a number of London street names, such as Rotten Row, whilst others such as Princes Street and Buchanan Street suggest a link with Edinburgh. A photograph of one such "marker" is included in the "Gallery of Images". Also included is a photograph of an obelisk which marks the battle Headquarters of the South Africans during the Delville Wood action. To the left rear of the museum is what is believed to be the last original tree to survive from before the war. This is marked by a plaque. The tree is a hornbeam and is situated near the Prince's Street-Regent Street intersection, behind the Museum. The Battle of Delville Wood was fought from 14 July to 3 September 1916. General Douglas Haig, Commander of the British Expeditionary Force planned to secure the British right flank, while the centre advanced to capture the higher lying areas of High Wood in the centre of his line and the Delville Wood battle was part of this effort to secure that right flank. The battle is of particular importance to South Africa, as it was the first major engagement entered into by the South African 1st Infantry Brigade on the Western Front. The casualties sustained by this Brigade were of catastrophic proportions, comparable to those encountered by Allied battalions on the first day of the Somme. On the Western Front, units were normally considered to be incapable of combat if their casualties had reached 30% and they were withdrawn once this level had been attained. The South African Brigade suffered losses of 80%, yet they managed to hold the Wood as ordered. The first major objective was to capture Longueval from the Germans but before this could be attempted the Allies had to first clear Trônes Wood as this posed a danger to their right flank as they approached Longueval from the south. They also knew that they would have to take Delville Wood which bordered the north eastern edge of Longueval as unless this was done Longueval would be difficult to hold as the wood could be used by German artillery to shell Longueval and would also provide ideal cover for the Germans to assemble reinforcements for a counterattack. To achieve this the 9th Scottish Division were to attack Longueval and the 18th Eastern Division under Major General Ivor Maxse on their right were to clear Trônes Wood. The Division Commander of the 9th Scottish Division, Major-General W.T. Furse ordered that the Longueval attack be led by the 26th Brigade. The 8th Black Watch and the 10th Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders would lead, the 9th Seaforth Highlanders would provide support and the 5th Cameron Highlanders would be in reserve. The 27th Brigade would follow, mopping up any bypassed German elements and providing support for the intense fighting which was expected once the leading battalions had entered the fortified town. Once the town had been secured, the 27th Brigade was to pass through the 26th to take Delville Wood. The 1st South African Brigade was to be kept in reserve. The offensive started at 0325 on 14 July and on a 4 miles (6 km) front but after fierce fighting it became clear to Major-General Furse that to secure Longueval, Delville Wood had to be taken first and as heavy losses were already being incurred he found that he had to commit the 1st South African Brigade to the fray. Furse ordered Brigadier General Henry Lukin to deploy his 1st South African Brigade to advance and to capture Delville Wood. The battle raged for several days, often with hand-to-hand fighting and with both sides incurring heavy losses. Throughout this period the German artillery pounded the wood from their positions in and around Longueval. In his 1983 book Ian Uys "Delville Wood" he quotes a German officer's words

The final German forces were driven from the wood on 3 September 1916 although the South Africans had been withdrawn at an earlier date. The Allies held the Wood until April 1918 when it was again re–captured by German forces during the "Spring Offensive" and held by them until 28 August 1918. On this day the 38th (Welsh) Division captured the wood for the second and last time. The war was to end three months later.[27] [28] [29]  |

Images of Delville Wood

[edit]-

Memorial avenue marker at Delville Wood. The trench systems were named after London and Scottish streets. This enabled the soldiers to identify features of the battlefield more easily.

-

South African Brigade HQ location memorial in Delville Wood.

-

Military Artist drawing of the Battle of Delville Wood, The Somme. July 1916

-

The South African Commemorative Museum

-

View of Delville Wood Cemetery

-

Plaque noting opening ceremony of the South African Commemorative Museum.

Memorial to the 20th Light Division

[edit]| Memorial to the 20th Light Division |

|---|

The British 20th (Light) Division was a New Army division formed in September 1914 as part of the K2 Army Group. The division landed in France in July 1915 and spent the duration of the war in action on the Western Front. The division fought at Loos, Mount Sorrel, Guillemont, Flers-Courcelette, Morval. Le Transloy, Messines and at Third Ypres and the Battle of Cambrai. The memorial shown here stands at Guillemont near to Delville Wood.[30]

Guillemont was a village to see much fighting in the Battle of the Somme. The Germans held on to Guillemont with great tenacity and after major attacks on 30 July and on 8 August, the village was finally taken on 3 September 1916. The 20th (Light) Division was instrumental in taking the village, one of the reasons for the choice of location, although there is another 20th Light Division Memorial at Langemarck in Flanders. The 16th (Irish) Division took nearby Ginchy on 9 September and there is a memorial to them near Guillemont. See below. This memorial is on the linas which was the division's target when they attacked on 3 September 1916. The road running north–south (which forms the cross-roads with the D20) was taken, as their third objective. The 20th Division Memorial is in fact a replacement of the original memorial. The original, a tapering stone obelisk, was unveiled on Sunday 4 June 1922, by Major-General Sir Cameron Shute (who had commanded the 59th Brigade of the 20th Division during the Guillemont actions). He was accompanied by the Mayor of Guillemont and a French Army representative (General Douchy), plus men who had fought with the division at Guillemont. The original memorial was similar in appearance to the same division's memorial in Flanders, which was unveiled five years after that at Guillemont. The Flanders memorial can still be seen today at Langemarck. The replacement memorial here at Guillemont was unveiled on 25 April 1995.[31]  |

Memorial to the 16th (Irish) Division at Guillemont

[edit]Guillemont Road Cemetery

[edit]| Guillemont Road Cemetery |

|---|

One of the best-known graves in this cemetery is that of Lieutenant Raymond Asquith, son of H. H. Asquith, who was Prime Minister at the time of his son's death on 15 September 1916. An obituary in The Times four days later recorded the loss of 'a man of brilliant promise'. He was a lawyer, and also following his father into politics (he was the prospective Liberal candidate for Derby) when the war broke out. Although already in his mid-thirties, he applied for a commission, and served initially in the Queens Westminsters, then the Grenadier Guards. He had applied to return to the frontline from a staff position shortly before he fought and died near here, and was obviously a brave and intelligent man. So the War, which is said to have touched most families in Britain, touched the lives of the Prime Minister, who lost his eldest son, and Raymond Asquith's own family. He left a wife and three children. From the cemetery there are good views across to the village church, and also Longueval church can be seen further in the distance. The buildings on the site of Guillemont Station can also be seen, and Trônes Wood is visible to the left.

|

Trônes Wood and the 18th Division Memorial

[edit]Guards Division Memorial on the road from Ginchy to Lesboeufs

[edit]The Memorial to the "Bradford Pals" at Hébuterne

[edit]| The Memorial to the "Bradford Pals" at Hébuterne |

|---|

The 16th and 18th (Service) Battalions of the Prince of Wales Own West Yorkshire Regiment 1914–1918 were part of what was known as "The Bradford Pals".

The tiny village of Hébuterne has a plaque on its church wall commemorating the Bradford Pals. The location was chosen because it is close to where 44 Pals were killed in woodland, but it is a couple of kilometres (miles) distant from Serre where the majority of them were mown down on 1 July 1916. The Bradford Pals had close associations with Bradford City Football Club and both battalions were admitted free to Valley Parade, the Bradford City ground, in the days leading up to their departure from Bradford. Their initial meetings took place at the Drill Hall right next to the ground and undoubtedly many of them will have been supporters of the Bradford City players Speirs, Torrance et al. Indeed, among the ranks of the Pals was none other than City's most famous player, the England international winger Dickie Bond, and fortunately he survived the conflict.[32] |

French Military Cemetery at Rancourt

[edit]| French Military Cemetery at Rancourt |

|---|

The village of Rancourt was captured by the French on 24 September 1916, and remained in Allied hands until 24 March 1918 and the German "Spring Offensive". It was recaptured by the 47th (London) Division on 1 September 1918. The French cemetery here is the largest French cemetery in the Somme area. It contains the remains of 8,566 soldiers of which 3,240 lie in ossuaries and stands as a testimony to the violent battles in the area in the final three months of the Somme offensive from September to November 1916.

There is a church alongside the cemetery and a small chapel on the other side of the road. This memorial chapel, built of dressed stone, was not the result of any official initiative but was funded by the du Bos family, originally from this region, who wished to commemorate their son and his comrades who were killed in action on 25 September 1916. The chapel was inaugurated by Marshal Foch in October 1923.[33]  |

German Military Cemetery at Rancourt

[edit]The Grévillers British Cemetery and the Grévillers Memorial

[edit]| The Grévillers British Cemetery and the Grévillers Memorial |

|---|

| Grévillers is a village 3 kilometres west of Bapaume and it was occupied by Commonwealth troops on 14 March 1917 and in April and May, the 3rd, 29th and 3rd Australian Casualty Clearing Stations were posted nearby. They began the cemetery and continued to use it until March 1918, when Grévillers was lost to the German during their "Spring Offensive". On the following 24 August, the New Zealand Division recaptured Grévillers. The Grévillers (New Zealand) Memorial stands within the Grévillers Cemetery and commemorates 446 officers and men of the New Zealand Division who died in the defensive fighting in the area from March to August 1918, and in the Advance to Victory between 8 August and 11 November 1918, and who have no known grave.

The cemetery and memorial were designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens. [35] |

Rancourt British Cemetery

[edit]| Rancourt British Cemetery |

|---|

| Rancourt is a small village on the main N17 road between Bapaume and Peronne and the British cemetery lies opposite the French Military Cemetery (see above). The cemetery was begun by units of the Guards Division in the winter of 1916–17, and used again by the burial officers of the 12th and 18th Divisions in September 1918. After the Armistice, six graves from the surrounding battlefields were brought into Row E. |

Memorial to the "Salford Pals" at Authuile

[edit]| Memorial to the "Salford Pals" at Authuile |

|---|

Authuile is a village 5 kilometres north of Albert. The village was held by British troops from the summer of 1915 to March 1918, when it was captured during the German "Spring Offensive."

On the wall of the rebuilt church, the picturesque porch of which is shown in the gallery below, is a bronze plaque celebrating the exploits of the "Salford Pals"; the 15th, 16th and 19th Lancashire Fusiliers of the 32nd Division. Also on the wall of the church is a memorial as shown below to some units from Glasgow. The dedication also shown in the gallery salutes the ties between the Scottish "Chardon "(Thistle) and the French "Coquelicote" (Poppy). [37]

|

The Australian Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux

[edit]| The Australian Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux |

|---|

The Villers–Bretonneux Australian National Memorial stands within Villers-Bretonneux Military Cemetery. Villers-Bretonneux became famous in 1918, when the German advance on Amiens ended in the capture of the village by their tanks and infantry on 23 April. On the following day, the 4th and 5th Australian Divisions, with units of the 8th and 18th Divisions, recaptured the whole of the village and on 8 August 1918, the 2nd and 5th Australian Divisions advanced from its eastern outskirts in the Battle of Amiens.

The memorial was erected to commemorate all Australian soldiers who fought in France and Belgium during the First World War, to their dead, and especially to name those of the dead who remains were not identified or who were listed as "Missing". Both the cemetery and memorial were designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and the memorial was unveiled by King George VI on 22 July 1938. There are now 10,762 Australian servicemen officially commemorated by this memorial and named within the register. The Villers-Bretonneux memorial was badly damaged in the course of the 1939–1945 War and file WO 219/922 held at The National Archives in Kew gives information on the damage sustained. Villers-Bretonneux is a sacred place for Australians and marks one of the seminal moments when the German's eventual defeat was started. The central arch of the memorial bears the crest of the Australian Imperial Force. The inscription, in French and English, reads

|

Newfoundland Memorial Park

[edit]| Newfoundland Memorial Park |

|---|

| It was at Beaumont Hamel that the Newfoundland Regiment and others attacked the German position known as "Y Ravine" and within minutes lost 710 men to the German Machine Gun located there. By nightfall 14,000 men were lost forever. The Memorial to the 51st Highland Division stands at the point where the Scots took the German line in November 1916.

The Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont Hamel stands in land which was purchased by the Dominion of Newfoundland after the First World War. It was named after the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, which had provided one battalion of 800 men to serve with the British and Commonwealth Armies. The park remembers their tragic part in the action of 1 July 1916, and also serves as a memorial to all the Newfoundlanders who fought in the First World War, most particularly those who have no known grave. The Newfoundland Memorial Park was opened on 7 June 1925 by Field Marshal Earl Haig. Newfoundland became a province of Canada in 1949 and the park is one of only two Canadian National Historic Sites outside Canada. The other National Historic Site is also in France at Vimy Ridge. The landscape architect for the design of the park was R H K Cochius. At the entrance to the park there is a bronze plaque with the following words inscribed on itThese are words written by John Oxenham (1852–1941) as a Memorial to the 29th Division. On the morning of 1 July 1916, as the Battle of the Somme began, the 29th Division was in action on the British Front Line in the location which is now Newfoundland Memorial Park. The division suffered a high number of casualties as a result of the success of the German defence in this sector. Many were cut down before they got anywhere near the German Front Line. Many were killed and wounded as they moved forward from the rear of the Front Line to follow on in the attack. The 29th Division was formed in the United Kingdom between January and March 1915. In mid March it was sent to Egypt, from where it sailed to take part in the Gallipoli Campaign, landing at Cape Helles on 25 April 1915. After 8 months of fighting in the Gallipoli Peninsula the 29th Division left Gallipoli on 7 and 8 January 1916, as part of the secret, silent evacuation of British troops from this fighting front. After a few weeks in Egypt the division was ordered to move to the Western Front. Passing through the Mediterranean port of Marseilles the 29th Division arrived in the rear of the Somme battle front from 15 to 29 March 1916. From this time the division was put into the British Front in the area north of the Ancre River, near to the German-held village of Beaumont Hamel. For the following three months the battalions in the division spent their time doing tours of trenches and training behind the lines to prepare for the large British offensive against the German position planned for the end of June. Following a 7-day artillery bombardment of the German Front and Rear areas, the battalions of the 29th Division were in position in their Assembly Trenches in the early hours of Saturday 1 July. At 07.20 hours the huge Hawthorn mine was blown on the left of the division's position. The leading battalions in the attack left the British Front Line trench at 07.30 hours. The Caribou memorial is one of 5 such memorials on the Western Front which commemorate the location where the 1st Battalion of the Newfoundland Regiment was in action. The caribou is the emblem of the Newfoundland Regiment. The sculptor of the bronze caribou was an Englishman called Basil Gotto The Caribou Memorial is situated on the high ground at the western side of the park, behind the British July 1916 Front Line, from where the 1st Battalion the Newfoundland Regiment began its advance on 1 July 1916. The shrubs around the rocks are native plants from Newfoundland. At the base of the Caribou there are three bronze panels listing 814 names for the Memorial to the Newfoundlanders Missing. These are Newfoundlanders who died on land and at sea in the First World War and who have no known graves. The other Caribou memorials are at Geudecourt near Bapaume, Harelbeke near Courtrai, Masnières near Cambrai and Monchy-le-Preux, near Arras. There are three cemeteries in the memorial park, the Hawthorn Ridge Cemetery No. 2, Hunter's Cemetery and Y Ravine Cemetery. The 51st (Highland) Division Memorial is also located in the park as it was on 13 November 1916 that the village of Beaumont Hamel was attacked and captured by the 51st (Highland) Division. This memorial was unveiled in 1924 and is a sculptured statue of a Scottish soldier in his kilt. He looks across the landscape over the Y Ravine and beyond the German Front Line where this successful action broke through. The sculptor was George Harry Paulin, A.R.S.A., F.R.B.S. (1888–1962) and the title of the sculpture was "Bronze Statuette – Memorial to 51st Highland Division at Beaumont Hamel 1924". The model for the sculpture was a company sergeant major in the division. The German regiment in the line at Beaumont Hamel was the 119 Reserve Infantry Regiment. The regiment had arrived in this sector in late September 1914, at which time it been engaged in a fight with the French Army. In August 1915 the French Army left this sector and the British Army took over. 119 Reserve Infantry Regiment, however, held this part of the German Front Line for 19 months as part of the 26th Reserve Division before the Battle of the Somme began on 1 July 1916. The German Front Line in the part of the sector at Y Ravine was situated at the bottom of a gentle slope. The British Front Line was situated a few hundred metres away on the higher ground of the slope. In spite of the pounding of the German Line by the 7 day British artillery bombardment before the attack on 1 July, most of the German soldiers had survived the shelling by sheltering in their protective bunkers. German accounts state that their nerves were frayed by the end of the 7 days, but their casualties were relatively light. When the British artillery fire was lifted a few minutes before Zero Hour of 07.30, the German soldiers at the bottom of the hill near Y Ravine were able to get back quickly into their battered trenches and man their machine guns. The British battalions making their way down the slope towards them were plain to see and were fired on by the German defenders as they approached them. The men of the Newfoundland Regiment moved forward at about 09.00 hours to follow on behind the leading battalion in the advance of 88th Brigade. Many of them were shot down trying to clamber over ground to cover the few yards from where they were in the rear of the British Front Line to start their advance down the hill. The Danger Tree is a petrified tree and the only original tree in this location to survive the 1914–1918 fighting in this location. [38]

|

Beaucourt Naval Division Memorial

[edit]| Beaucourt Naval Division Memorial |

|---|

| File WO 32/5891 held at The National Archives in Kew covers the Royal Naval Division Memorial at Beaucourt. Correspondence in the file runs from 1921 to 1923. We learn that Alan G Brace designed the memorial and the land on which it stood was purchased for 200 francs from a Madame Maison. The memorial is in the form of a tall obelisk. There are bronze plaques on the front, the main one explaining that the memorial honours those men of the Royal Naval Division who fell at the Battle of the Ancre during the final phase of the Somme battles, on 13 and 14 November 1916. When the Royal Naval Division Memorial Committee was seeking to put a monument in place in 1921, Lord Rothermere offered to provide funding, as his son, Lieutenant the Honourable Vere Harmsworth had been killed in the Battle of the Ancre. He is buried in Ancre British Cemetery. With the help of this funding, the memorial was unveiled on 12 November 1922. The position it stands on was No Man's Land during the battle, and at the time of the unveiling the land still bore the scars. The unveiling ceremony was performed by General Sir Hubert Gough along with Brigadier-General Arthur Asquith, and around 200 officers and men of the Royal Naval Division who had fought there were also present. |

The Piper's Memorial at Longueval

[edit]| The Piper's Memorial at Longueval |

|---|

At Longueval there is a memorial to all the pipers who fell in the 1914–18 War. It was inaugurated on 20 July 2002 and was sculptured by Andy DeComyn. It shows a piper in full battle dress, kilt and tin helmet climbing up and over the parapet of a trench and encouraging the men on with the sound of his pipes.

It is said that the sound of the Bagpipes frightened the Germans to death in both World Wars and in the 1914–1918 war the Germans called the kilted Highlanders the "Ladies from Hell". Two pipers deserve mention, Pipers Laidlaw and Mackenzie. On 25 September 1915, the first day of the Battle of Loos, Piper Laidlaw was awarded the Victoria Cross. At a point where the men of the 7th Kings Own Scottish Borderers were in some confusion, crouched in their trenches when the gas clouds rolled back to engulf them, it was the sound of the pipes played by Piper Laidlaw, heard above the noise of the German guns, and falling shrapnel, which first steadied and then galvanised the line. Piper Laidlaw had jumped onto the parapet, torn off his mask, and begun to play his pipes! It was as though the Scots had had a massive injection of adrenalin, and soon they poured over the top and massed towards the German Lines, as Laidlaw marched up and down playing "The Standard on the Braes O'Mar" and the regimental march, the "Blue Bonnets". It was said that Laidlaw had every drone shot off his pipes, and the bag punctured in several places. We can read the exact citation in WO 98 at The National Archives. Loos is of course covered in the Artois section of this article so this is a slight digression. During the same battle the 6th Battalion Kings Own Scottish Borderers were similarly inspired by the pipes of Pipe-Major Robert Mackenzie. Mackenzie was 60 years of age, and although wounded had continued to play his pipes. He died on 8 October 1915. We can see both Laidlaw and Mackenzie's medal index cards in WO 373 at The National Archives.  |

The McCrae's Battalion Memorial

[edit]| 16th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Scots |

|---|

A tribute to McCrae's Battalion, the 16th Royal Scots, is to be found at Contalmaison where they fought on the opening day of the Battle of the Somme. The cairn remembers in particular players and supporters of Heart of Midlothian Football Club who made a significant contribution to the make–up of the battalion. The Contalmaison Cairn (designed by historian, Jack Alexander) was completed in 2004 and dedicated before a crowd of over 800 battalion families; Hearts, Hibs, Falkirk and Raith Rovers supporters; Royal Scots and government representatives.

The 16th (Service) Battalion (2nd Edinburgh) was known as Sir George McCrae's Battalion or (more familiarly) "McCrae's Own". Thirteen players from Heart of Midlothian joined up in November 1914 when Hearts were top of the Scottish League. Professional footballers from Raith Rovers, Dunfermline Athletic and Falkirk, and amateur players from Dalkeith Thistle, Linlithgow Rose, Newtongrange Star, Pumpherston Rangers and West End Athletic joined McCrae's Own as did other sportsmen, along with many Hearts and Hibernian supporters. Hearts player Alfie Briggs was wounded so badly at the Somme that he was discharged. [40]  |

Gallery of images

[edit]-

The Piper's Memorial at Longueval

-

The church alongside Rancourt French Military Cemetery

-

Portrait of Raymond Asquith (1878-1916) published in "the Sphere" on 23 September 1916, eight days after Asquith's death

-

Ossuary at Serre-Hébuterne French Military Cemetery

-

View of Pozières Memorial

-

Memorial to York and Lancasters near Serre.

-

Inscription on Thiepval Memorial.

-

One of the roundels on Thiepval Memorial. These roundels mark all the engagements in which the British Army fought.

-

Memorial in Anglo-French cemetery behind the Thiepval Memorial.

-

Pozières welcomes Australians. As one enters Pozières one is greeted by a painting of an Aussie soldier.

-

English: British Vickers machine gun crew wearing PH-type anti-gas helmets. Near Ovillers during the Battle of the Somme, July 1916. The gunner is wearing a padded waistcoat, enabling him to carry the machine gun barrel.

-

Cross by Lochnagar Crater at Ovillers-la-Boisselle.

See also

[edit]- List of World War I Memorials and Cemeteries in Alsace

- List of World War I memorials and cemeteries in the Argonne

- List of World War I memorials and cemeteries in Artois

- List of World War I memorials and cemeteries in Champagne-Ardennes

- List of World War I memorials and cemeteries in Flanders

- List of World War I Memorials and Cemeteries in Lorraine

- List of World War I memorials and cemeteries in Verdun

- List of World War I memorials and cemeteries in the area of the St Mihiel salient

Further reading

[edit]- Alexandre Thers. "La Somme L'offensive traqique". ISBN 2-913903-67-3

- "Illustrated Michelin Guides to the Battlefields (1914–1918)". ISBN 0 904775 14 3 and 0 904775 19 4 both cover The Somme, the first in 1916 and the second in 1918.

- "Michelin's Illustrated Guides to the Battlefields (1914–1918). Amiens". ISBN 0 904775 59 3.

- Ian Uys. "Longueval". ISBN 0 620 09532 6

- Ray Westlake. "Kitchener's Army" ISBN 1-86227-212-3

- "Illustrated Michelin Guides to the Battlefields (1914–1918). Soissons" ISBN 0 904775 89 5.

- G. Gliddon. "VCs Handbook. The Western Front 1914–1918" ISBN 978-0-7509-3545-6

- P. Longworth. "The Unending Vigil" ISBN 1 84415 004-6

- M. Brown. "Book of the Somme" ISBN 0-283-06249-5

- Ian Uys. "Delville Wood" ISBN 0 620 06611 3

- A.H. Farrar-Hockley. "The Somme" ISBN 0 330 28035 X

- Lyn MacDonald. Somme ISBN 0-333-36648-4

- Chris McCarthy. "The Somme. The Day-by-Day Account" ISBN 1-85409-330-4

- Jack Alexander. "McCrae's Battalion" ISBN 1-84018-932-0

References

[edit]- ^ Memorial to the Liverpool and Manchester Pals at Montauban World War One Website. Retrieved 11 January 2013

- ^ Memorial to the Liverpool and Manchester Pals at Montauban Sacred Ground. Retrieved 11 January 2013

- ^ 7th Yorkshire Regiment Memorial at Fricourt www.webmatters.net. Retrieved 17 January 2013

- ^ Statue of Marshal Foch at Bouchavesnes Images de Picardie. Retrieved 17 January 2013

- ^ Memorial to 18th Division at Thiepval www.firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 16 January 2013

- ^ Memorial to the 46th Division at Bellenglise www.ww1cemeteries.com Retrieved 16 January 2013

- ^ Flers www.firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 16 January 2013

- ^ New Zealand Memorial at Longueval www.firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 16 January 2013

- ^ New Zealand Memorial to the Missing at Caterpillar Valley Cemetery Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 16 January 2013

- ^ 38th Division Memorial Mametz Wood Australian Government Website. Retrieved 11 January 2013

- ^ 38th Division History www.1914–1918. net. Retrieved 11 January 2013

- ^ Joint Memorial to the Black Watch and Cameron Highlanders WWI Battlefields. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ^ Australian 1st Division Memorial Australian Government Website "WW1 Western Front". Retrieved 13 January 2013

- ^ Australian 1st Division Memorial Great War Website. Retrieved 13 January 2013

- ^ Tank Memorial at Pozières Great War Website. Retrieved 13 January 2013

- ^ Windmill Memorial at Pozières Australian Government Website "WW1 Western Front". Retrieved 13 January 2013

- ^ [1] Australian Government website. Retrieved 12 January 2013

- ^ The Kings Royal Rifle Corps Memorial www.Webmatters.net. Retrieved 13 January 2013

- ^ Laurence A. Turner Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851–1951, University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII, online database 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2013

- ^ The Pozieres Memorial Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 12 January 2013

- ^ The Ulster Tower WW1 Battlefields Website. Retrieved 13 January 2013

- ^ The Ulster Tower WW1 Cemeteries Website. Retrieved 13 January 2013

- ^ The Canadian Memorial at Courcelette WW1 Battlefields. Retrieved 13 January 2013

- ^ Lochnagar Great War Website. Retrieved 17 January 2013

- ^ a b "World War One Battlefields : The Somme : Ovillers & la Boiselle". www.ww1battlefields.co.uk. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ The 34th Division Memorial at La Boiselle www.webmatters.net. Retrieved 13 January 2013

- ^ Delville Wood www.delvillewood.com. Retrieved 14 January 2013

- ^ Delville Wood WW1 Battlefields. Retrieved 14 January 2013

- ^ Battle of Delville Wood, 15 July – 3 September 1916 Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 14 January 2013

- ^ 20th Light Division www.1914–1918.net. Retrieved 14 January 2013

- ^ Guillemont WW1 Battlefields. Retrieved 14 January 2013

- ^ Memorial to Bradford Pals Bradford City Website. Retrieved 14 January 2013

- ^ Rancourt French Cemetery Western Front Website. Retrieved 15 January 2013

- ^ Rancourt German Cemetery www.webmatters.net. Retrieved 15 January 2013

- ^ The Grevillers British Cemetery and the Grevillers Memorial Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 15 January 2013

- ^ Rancourt British Cemetery Archived 20 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine WW1 Cemeteries. Retrieved 15 January 2013

- ^ Memorial to the "Salford Pals" at Authuile www.hellfire-corner.demon.co.uk. Retrieved 15 January 2013

- ^ Newfoundland Memorial Park Great War Website. Retrieved 17 January 2013

- ^ Beaucourt Naval Division Memorial www.webmatters.net. Retrieved 17 January 2013

- ^ Heart of Midlothian Memorial WW1 Batlefields. Retrieved 16 January 2013

External links

[edit]- France-Searchable French website Enables searches to be made for French soldiers killed in 1914–1918

- Australia- Australian Government website covering the Australian Imperial Force An excellent website for matters concerning the Australian Imperial Force.

- Canada-Canadian Government website Again has facilities to search for Canadian service records of the 1914–1918 war.

- Germany-German website Comprehensive details of German cemeteries, etc.

- Battle of the Somme

- World War I cemeteries in France

- World War I memorials in France

- Battles of the Western Front (World War I)

- Buildings and structures in Somme (department)

- Cemeteries in Hauts-de-France

- History of Somme (department)

- Tourist attractions in Somme (department)

- Lists of cemeteries in France

- Lists of war monuments and memorials in France

- Lists of World War I monuments and memorials